With high demand for careers in STEM, why do the odds seem stacked against women in Australia? And what opportunities do we have to overcome it?

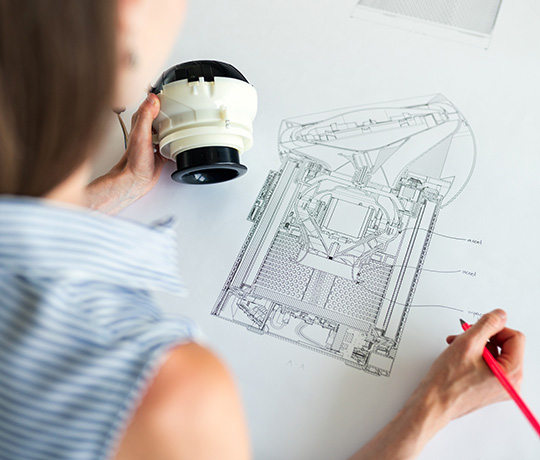

In a world with an increasing interest in technology and innovation, we need our innovators to constantly be on the cutting edge of forward thinking. And we need all our best minds in the labs. STEM – a field that refers to science, technology, engineering and mathematics – will have some of the most important roles for our bright young minds.

There’s just one little problem – there are currently hardly any women in STEM.

So where are the women in STEM?

The value of women’s contributions to these areas cannot be understated. Some hotshot ladies in STEM throughout history include Marie Curie, Rosalind Franklin, Chieng-Shiung Wu, Dame Jocelyn Burnell, Elizabeth Blackburn, Jennifer Doudna and Emmanuelle Charpentier, just to name a few. It’s clear how much STEM needs women just from this impressive list, if not also for the general demand for STEM workers in general. According to PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC), upskilling just 1% of the Australian workforce into STEM roles would add $57 billion to Australia’s gross domestic product over 20 years. With women making up 52% of the Australian population, it makes sense why we would want half the population to have the opportunity to participate. So what doesn’t make sense is why they make up only a third of all STEM graduates. And are then are shaved down to a tiny 16% of the STEM workforce.

Growing up with gender norms in 2020

Societal gender norms and binaries are still rampant in the 21st century, with little girls encouraged more than boys to play with dolls or in kitchens. This continues into their teenage years, where pubescent girls are encouraged to concern themselves with their body and appearance. By adulthood the media reinforces traditional gender roles of women at home and the men as the breadwinners. None of these biases encourage women to chase their intellectual pursuits. This mindset is enforced from childhood, as early as primary school. So by age nine, when asked to draw a scientist, children are more likely to draw a man.

Young Australian girls are also less confident when it comes to performing in science and math subjects when compared to their male counterparts – only a third feel confident, as compared to 44% of boys. However, a 2011 Psychological Bulletin analysis shows no significant difference in mathematics performances when boys and girls are given the same standardised test. Additionally, behavioural ecologist Shinichi Nakagawa used a sample of 1.5 million students across English speaking countries to test STEM grades and found that in a simulated classroom environment, the top 10% of STEM students would be evenly distributed across boys and girls. So why does this even distribution not carry over? By year twelve, boys outnumbers girls 3:1 in physics and 9:1 in advanced maths.

The numbers decrease even more so by university – in undergraduate degrees, a 2016 report by Office of the Chief Scientist show that women only account for 13% of IT graduates; 14% of engineering graduates; 22% of physics graduates; 33% of math graduates; 36% of earth sciences graduates; and 42% of chemistry graduates. In non-STEM areas, women account for 65% of all undergraduate degrees.

By the time women STEM graduates enter the workforce in severely lesser numbers compared to men, the hurdles don’t seem to stop. STEM employers are less likely to employ women, with the least inclusive industries being construction and transport. There are many reasons for this inequality – one being that women continue to earn less than men who occupy identical roles, including in STEM. Pay inequality remains an issue all across Australian industries, and within STEM 32% of males earn above $104,000, compared to just 12% of the females.

Furthermore, women may also face sexual harassment, unconscious bias and discrimination in the workplace. In a study conducted by Corinne Moss-Racusin, employers were presented with identical resumes to which male and female names had been assigned randomly. Employers tended to rank the ‘male’-presenting applicants higher and offer them better salaries. Due to lower pay, job insecurity and limited career prospects, it’s no wonder women are hesitant to pursue their dreams in STEM. It’s a long, slow, progressive squeeze-out, and the lack of women in STEM represents a significant waste of knowledge, talent and overall benefit for Australian advancement.

So, what can we do to fix this? What’s the good news?

The lack of women in STEM fields has garnered considerable notoriety and attention, resulting in a number of outreach programs and support networks for women considering or already in STEM. It’s agreed that systematic changes need to happen from an early stage. Teaching STEM subjects as fun and engaging for young girls, so they learn to consider careers in this field. Organisations such as Code Like A Girl work to provide young girls with tools and knowledge required in STEM subjects. Code Like A Girl runs school holiday camps for girls aged 8-15 as well as workshops for adults and internships, working to empower women to be and achieve anything they want.

In 2016, the government announced $8 million of funding for projects supporting women in STEM, with similar initiatives such as Science in Australia Gender Equity (SAGE) and Male Champions of Change. There’s an abundance of outreach programs, mentorships and scholarships specifically for young women seeking to study STEM in university. Society is slowly but surely understanding the need for more gals in math and sciences, and we’re getting there little by little. It takes time to change up an imbalanced system.

So if you’re a girl thinking about STEM – do it! There are resources out there for you to help even out the playing field, and Australia needs you! We need your mind, your talent, every dream and aspiration you have to offer. As you know, STEM has historically been a difficult landscape for women. But it’s changing every day, improving every day, and your mind is destined for the best.

“Don’t give up, continue to do what you’re passionate and excited about. It’s likely that you’ll often be the only woman in the room, the only woman on the team, or sometimes the entire office — but don’t go at it alone, there are many women in the same situation and find ways to connect in with them to support each other.”

Vanessa Doake, co-founder of Code Like A Girl,